With the financial support of

With the support of

Synopsis:

Viktor Valerevich Mumikhotkak also known as „Mukha“, Chukchi from the hamlet New Chaplino (Chukotka, Russia), died tragically in 2012. Somebody stabbed him in his abdomen and cut off his fingers. In 2014, when young Alla Ukuma gave birth to her first son, her mother told her: „Last night I saw Mukha in my dream. He had come back in your boy. Let us name your baby Viktor.“ According to the local people, the dead can return to the realm of the living up to five times. This film essay on life, death and possible return poses the universal question: How do you confront your own end?

production: Jaroslava Panáková and PAMODAJ Community | postproduction: High-Tech Media studio | starring the local people of New Chaplino and Yanrakynnot | music and sound design: Jonatán Pastirčák | editing: Šimon Špidla | photography: Jaroslava Panáková and children from New Chaplino and Yanrakynnot | direction: Jaroslava Panáková

Of Place and Men

This movie portrays people of Chukotka villages, Eskimo people Yupiget and Chukchi who live on the farthermost northeastern tip of Russia. Although the place is so remote and unknown, the subject of the film – life and death – is intimate and humanly universal at the same time. The issue behind the film starts off with what is out of focus: Mortality in Chukotka remains high even in the age of globalization (e.g. in 1990 the average life expectancy in Chukotka was 49 years, while in the rest of Russia’s the average value was 68 year). In the early 20th century, the most frequent cause of premature death was a hunting accident, in 1950s it was tuberculosis, and since 1970s it has been violent death (homicide, suicide) or accidental fatalities (drowning, hypothermia) (Pika 1996).

Merciless statistics have personal meaning to me. Since 2008, I have travelled to the village Novoye Chaplino and Yanrakynnot. In this part of the Russian Far East, where the traditional subsistence economy consists of marine hunting and reindeer herding, along with fishing and bird hunting, the special relationship between the tundra and the sea can be well observed. Novoye Chaplino, located in Tkachen Bay, numbers about 400 inhabitants of Chukchi and Yupik origin. About 300 people, mainly Chukchi, live in Yanrakynnot. Their livelihood is based on both marine hunting and reindeer herding. These villages were created artificially by the Soviet government under the policy of bringing the population into fewer larger villages near the centre (politika ukrupnenia). Two years ago, almost all houses in these villages were replaced with new turnkey buildings.

During my visits of this remote place, my friends have been „leaving“ literally before my eyes. They often expose themselves to deadly risk and die young: Alexei Nutangli, 33, battered to death in 2009, Akilkak’s son, Eduard Akilkak, 46, car accident in 2010, Slava Burdin „Burdos“ stabbed to death by a friend in a fight in 2012. During my visits or between them, several people, whom I had filmed, died: Yevgenia Numynkau hung herself in 2012, Viktor Mumichotkak was stabbed to death in 2012, Alexander Kymyjochkin got poisoned with industrial alcohol in 2014. Such deaths occur every single year and the number of such tragic incidents is striking compared to the total population of the village. It was only after several of my close friends had died that I started to consistently ask the question why a person allows to be pulled out of the life cycle before time. The volition to depart has its own reasons, and I know nothing of these. I ask about them, but despite their frequent occurrence, locals do not like to speak about death. While watching everyday moments of happiness, we also witness the „trivial“ death of a reindeer, a whale, or a bird. People’s statements about those who are gone may sound equally negligible. At least they always try to hush it up by saying „It’s snowing“ or something of the kind. All in all, happiness that is lived may also look banal.

On Returning

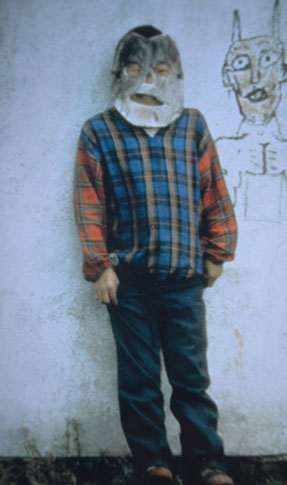

Yupik Eskimos and Chukchi believe that the world and life are cyclical. There is only a limited number of souls who live either here on Earth or in the world of the dead, which itself is divided into lower and upper world. Man does not die, but instead his/her soul returns to the world of ancestors. The dead relatives decide whether the next return to the world of the living is possible and who that might be. If a soul is allowed to reappear in the world of the living, it will do so through a name. In this way, a particular name may be given to a newborn five times, irrespective of gender – female name can return as a man and male name as a woman. Sometimes a name reappears concurrently in several persons. These two stories illustrate the return of a name: 1. When a baby girl was born, an old woman came and said: „I had a dream about Inata the last night, he has returned through her“. And so, although the baby had been given name Ekaterina, Inata will be her other name. Sometimes a baby has some body signs that resemble a deceased ancestor. However, this is not a reincarnation. Ekaterina has her own personality and Inata his own. Yet they are connected through common memory and duties. If Inata was a grandfather’s cousin, Ekaterina is now not only her mother’s daughter but also her mother’s uncle of the second order. Thus her affiliations to people, whether blood relatives or not, are doubled and her further obligations towards these other relatives are defined. 2. When I was in Novoe Chaplino in the summer 2014, I met a young couple, Alla and Pavel, with their firstborn son Viktor. They told me that Viktor Mumikhotkak has returned through their son. Viktor Mumikhotkak had died two years earlier, he was stabbed to death and his finger were cut off. Baby Viktor has his life before him. However, it is already apparent that he „knows“ the place, people around him, and the smell of tundra and sea, the same way Viktor Mumikhotkak did.

On Food

Life can be threatened by a number of circumstances. They are caused by evil spirits. The spirits are everywhere and can harm people anytime. Death is omnipresent. Death must be driven off every instance. Both the deceased ancestors and the spirits must be constantly comforted. Everyday is a continuous effort of gaining their affection. This can be achieved through feeding (akh’ky’siakh’mul’yk’). While walking in tundra and arriving to a place where certain people used to live, one should sit down, build a fire and just before eating, s/he shall throw a little food into the fire. Offering the spirits a cigarette, alcohol or some sweets is also welcome. When at home, one should throw a crumb of food into the corner or into the stove. These are everyday acts, performed along with other common daily tasks, such as hunting, cutting meat, walking about tundra, going to work or school, visiting neighbors and so on.

On film

A film essay about life, death or possible return does not portray dying explicitly. In the entire film, there is not one scene that would be expected for an etnographic documentary about human death – a funeral ceremony, funeral festivities, or a burial. Death as dying, absence, forgetting, missing someone or feeling emptiness, these all appear only as hints. The issue of death is presented on the background of rather plain conversations between a son and a mother and wandering in the tundra, in widows’ testimonies, during flensing or children’s games. Life – or mere indulgence – predominates even at the memorial services. Observing life is the way to answer some questions about death, or at least to touch them off.

The film, however, offers several occasions to observe animal death. A cormorant trapped in a fishing net. Whale flencing on the shore. Men dodging disorderly and sluggishly along the shore, looking for a rope, sharping a knife, clumsily trying to turn the dead whale onto the other side. Death of a reindeer. Dying can be most clearly seen in animal eyes. The fragments of life are interlaced with the sense of death: children are playing, they are running across the village, they enjoy a ride on the merry-go-round. These images are not quite innocent. They appear as mockery and violence. As if even kids foresee the possibility of being gone anytime. Only their sleep seems to be peaceful. The conversations between young lads and their mothers are stressful. Perhaps it is a psychoanalytical stereotype. I have noticed that the men are not any heroes. Often their souls are hurt and they have no one to confess to. They must appear “cool” among their peers, strong in the eyes of local girls, and competitive with their fathers. The only person who takes them as they are is their mother. Children learn to communicate with animal soul. If they succeed, they will be able to sacrifice it instead of themselves and thus prolong their own life. Children have recorded a sequence where they play near the tent (yaranga) and try to catch a reindeer with a lasso. A girl holds antlers on her head, a boy is chasing her and throws a lasso (chaat) onto her. An adult herder tries to do the same. The interviews with women make me silent: mother who lost her daughter and son, young woman who lost her husband, Evgenia who thinks of suicide (and in several months she would be gone). “Where do you live? What keeps you going?”, she asks me. Some memories from my home: shadows from my home town, acrobats walking the rope, a windmill… A boy is walking across a snow-covered plain, dropping a tea-kettle all the time, astray, delirious, someone calling his name. We don’t know where we are going. I feel sad for Evgenia. For me, it is hard to believe she will come back one day. Perhaps I think too much as a European. Perhaps I ask questions that should stay hidden. I wonder: all the locals, no matter what age, know how to make knots. Why the knot, normally used by sea mammal hunters to tie a catch to their boat, thus bringing the necessary food to the village, is used by Evgenia to take her life? I follow the beat of my heart. The speech of death makes it louder. The clear sound assures me of being still here.

On experience with children

I came to Chukotka at the age when my Yupik and Chukchi peers have already had their children. Excited about my origin and my camera, local kids began to visit me and take walks with me. I was afraid that some of them, especially those with parents afflicted with alcoholism, visited me only because of the “hell” they suffered at home. I also didn’t mean to ruin my relations with their parents. I tried to remain true and not to yield to Helper Syndrome. I wished to overcome our mutual excitment about “the new” and “the unknown” and build a stronger relationship between us. They showed me “their places”, even the secret ones. They were asking curiously. They asked me to fill their time with something that was fun and I, in turn, was curious about the way they see their village. So I began to lend them my camera, and later even the movie camera. Some of the kids had their own photo cameras. My camera captured their attention with the size of its lens and the number of functions. They preferred the automatic mode. Setting shutter and manual focus made them tired. Shooting with a 8mm camera disappointed them, since they could not see the result immediately on the LCD monitor. After the initial enthusiasm (mutual portraits, shots of ground, flowers, sea etc.), they started to film various everyday events. I limited my guidance by suggesting some topics and ways of manipulating with the camera (e.g. “Try to direct the camera at one object or a person and watch what is happening to them, and not to wave the camera aimlessly at everything you see.”). I felt most connected with the children when shooting by yaranga (traditional tent) in tundra. I sensed my own freedom and so I could really appreciate their own. When we tried to shoot interviews, I tried to guide children in how to ask the questions and record the sound. Sometimes I even acted like a strict teacher and felt worthless. However, I believe we have experienced together some really great moments. The images made by children themselves form an essential part of the film. This is to thank them for “being there”.

PAMODAJ Community

Address: B. Němcovej 4035/2, 03601 Martin , Slovakia

Identification number: 42391491

Tax number: 2024185878

Contact person: Jaroslava Panáková